Network notes don’t usually become public. This one did—and it stings. In recent interviews, Marlon Wayans said NBC rejected John Witherspoon as “Pops” on The Wayans Bros., calling the veteran comic “too ghetto,” “too country,” and “too Detroit.” The brothers were told to swap him for a more polished, Danny Glover–type father figure—or lose the slot entirely.

Wayans recounted the moment on Keke Palmer’s Baby, This Is Keke Palmer podcast and Shannon Sharpe’s Club Shay Shay, describing an early table read where NBC executives balked at Witherspoon’s take on Pops, a loud, loving, working-class dad. The feedback wasn’t subtle. The network wanted a safer, tidier version of Black fatherhood. The Wayans brothers said no.

NBC notes and the ultimatum

According to Wayans, NBC handed down a clear choice: replace Witherspoon or the show wouldn’t make air. Executives floated a “Danny Glover type” as the model—familiar, respectable, and far from the rough edges that made Pops feel real. “Either you replace the father or you don’t get on our air,” Wayans remembered them saying.

The brothers pushed back. They believed Witherspoon’s Pops—brash, warm, and proudly blue-collar—was the spine of the show. He wasn’t a caricature; he was specific. He sounded like Detroit, moved like a guy who’d worked a register, and parented with jokes and tough love. Toning that down, they felt, would gut the show’s identity.

So they walked. That’s rare in broadcast TV development, where countless projects bend to survive the note-giving gauntlet. But the Wayans family had leverage—fresh off In Living Color’s cultural jolt—and a clear sense of what they were building.

What happened next is TV serendipity:

- The WB, a brand-new network at the time, picked up The Wayans Bros. with Witherspoon intact.

- The show premiered in 1995 and ran for five seasons, becoming a cornerstone of The WB’s early comedy slate.

- Pops became one of Witherspoon’s signature roles, right alongside Friday and his later voice work on The Boondocks.

How The WB turned a pass into a hit

When The Wayans Bros. landed at The WB, the network was searching for identity. It launched in 1995, the same year as UPN, targeting younger, more diverse audiences that the big three often underserved. The Wayans’ sitcom fit that mission—looser, louder, and unapologetically specific. Witherspoon’s Pops was the heartbeat.

The show followed two brothers running a newsstand inside a Manhattan mall, but the family dynamics did the heavy lifting. Pops wasn’t aspirational in a country-club way; he was aspirational in a survival way. He was chaotic, hilarious, broke sometimes, and always present. Fans still echo his “Bang! Bang! Bang!” catchphrase decades later.

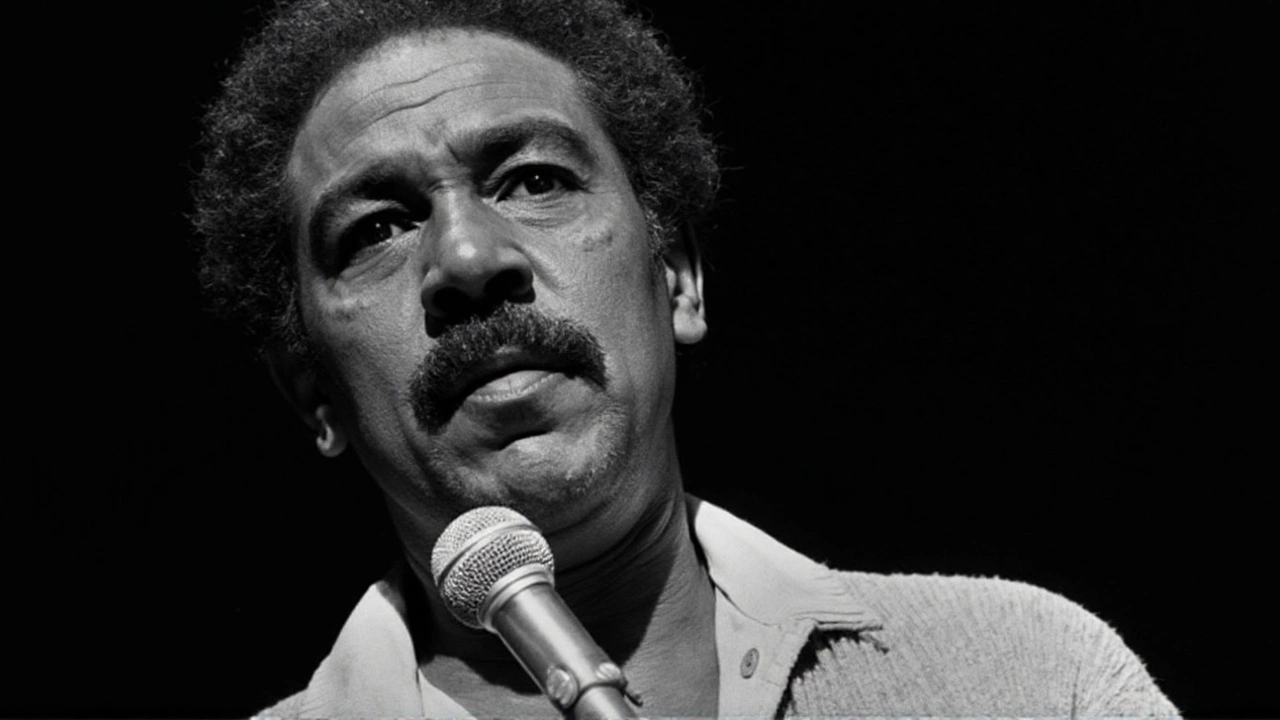

Witherspoon, who died in 2019 at 77, had been building that voice for years—club sets, scene-stealing turns in House Party and Boomerang, then Friday in 1995. On The Wayans Bros., he channeled all of it into a TV dad who felt lived-in, not lab-grown. That’s the tone NBC tried to iron out and The WB embraced.

Wayans framed the detour as a blessing. “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” he said, adding that the closed door with NBC simply pointed them to the one that mattered. The result: five seasons, a loyal fan base, and a role that still defines Witherspoon’s TV legacy.

The incident also reveals how network language can work. Labels like “too ghetto” or “too Detroit” don’t just critique a character; they police who gets to be centered on mainstream TV. In the mid-90s, NBC already had hits with Black families—The Cosby Show and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air—but those centered middle-class stability. Pops represented working-class Black life with sharper edges and louder humor. That contrast spooked the room.

Industry veterans will tell you this is how pilot season often goes: table read, notes, compromises, and sometimes a quiet burial. Most creators take the tweak to stay alive. The Wayans brothers didn’t, and that’s precisely why their story sticks. They gambled on chemistry they believed the audience would recognize instantly.

The WB’s early comedy block—a mix that would later include The Jamie Foxx Show and other talent-driven sitcoms—found loyal viewers by letting performers be themselves. The Wayans Bros. wasn’t a ratings monster by modern standards, but it became one of those weeknight shows that people still quote and stream today. It also helped give The WB a comedic tone that balanced teen-focused dramas like Dawson’s Creek later on.

There’s also the simple matter of what TV lost when executives tried to reshape Pops. Witherspoon’s timing—those tossed-off asides, the freewheeling riffs, the dad energy that could turn from scolding to cackling in a beat—wasn’t interchangeable. You couldn’t swap him out and get the same show. You’d get a different, safer sitcom. And probably a forgettable one.

Wayans’ retelling lands in a different Hollywood, one that publicly vows inclusion and authenticity but still wrestles with who gets greenlit and how they’re framed. Network gatekeeping has shifted to streaming data and algorithmic bets, yet the core debate is familiar: do you chase comfort, or do you back something specific and real?

NBC didn’t end up hurting for hits in the mid-90s—it was the Seinfeld and Friends era—but it did pass on a show that helped launch a rival network’s identity. The Wayans Bros. proved that the thing some executives flagged as a problem—the texture of Pops—was actually the asset. Audiences knew it, The WB trusted it, and Witherspoon delivered it.

That’s why this story resonates. It’s not just a peek at old notes; it’s a reminder of how easily TV can sand down what makes characters memorable. In this case, the creators held the line, the right door opened, and the version that made people laugh the hardest made it to air.